Peggy Spaeth and John Barber, co-chairs

Article by Peggy Spaeth

Many of us have been walking, running, bicycling, birding, and botanizing in the Shaker Parklands for decades, in all kinds of weather. These man-made lakes are a treasured place embedded within the residential cities of Cleveland Heights and Shaker Heights, and are a regional destination as well.

We are very alarmed by the condition of the habitat around the lakes. We know that a healthy ecosystem is complex. Yet here the habitat is increasingly simplified by grass and invasive species that do not feed native birds and insects, that outcompete native plants, and that spread throughout the watershed. Please remember that these parks are designated an Audubon Important Bird Area. How are we feeding the warblers that migrate on this route twice a year if their native food sources are disappearing?

Conventional thinking about leaving public parks to naturalize is misguided. The complex balance of native plants, insects, and mammals is now too disturbed to “let nature take its course.” There are several overlapping entities involved in the management of the lake, including the cities of Cleveland Heights and Shaker Heights, who hold leases from the city of Cleveland; the Shaker Parklands Management Committee; Doan Brook Watershed Partnership; and the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District. It is typical, efficient, and economical for cities to “mow and blow” rather than create and maintain habitat and our cities are no different. But we can do better if we want to live in a place healthy for insects, birds, and ourselves.

So we asked, “Whose responsibility is it to restore and maintain a healthy habitat at the lakes?” In the end, we realized it is ours.

Although our intention is habitat restoration, we have inadvertently discovered rich local history by simply starting to remove porcelain berry at the concrete canoe launch. This history has been one of the most fascinating parts of the project, both to volunteers working at the site and the ever-present stream of people and dogs coming by while we’re working. Here is what we found out about the lake, and what we are doing:Why is there even a lake there? Before settlement, this site was a forested ravine. (Ohio was 95% forested in all.) When European settlers arrived in northeast Ohio, they made claim to land occupied by Native Americans through, as one author wrote, “unwelcome treaties and paltry payments.”

Surveys were completed during the period of 1790 – 1807 that focused on laying out townships and inventorying trees for logging. The most common trees found in the Doan Brook watershed (as its called today) were Beech, Oak, Maple, and Chestnut.

The Shakers formed the North Union Colony in the 1820’s in this area. They constructed several dams, the largest of which was built in 1836 to form today’s Lower Lake, for the purpose of having a water-driven sawmill. They cleared the trees in the ravine, then used those trees, clay, and rocks to build the dam.

The colony disbanded in 1889 and the gristmills, sawmill, woolen mills and buildings were torn down (or blown up in the case of the biggest gristmill) and today only a few foundations remain.

Developers then purchased the lands around Lower Lake for housing. The lakes have been considered an asset to the residential community since then, often featured in real estate ads.

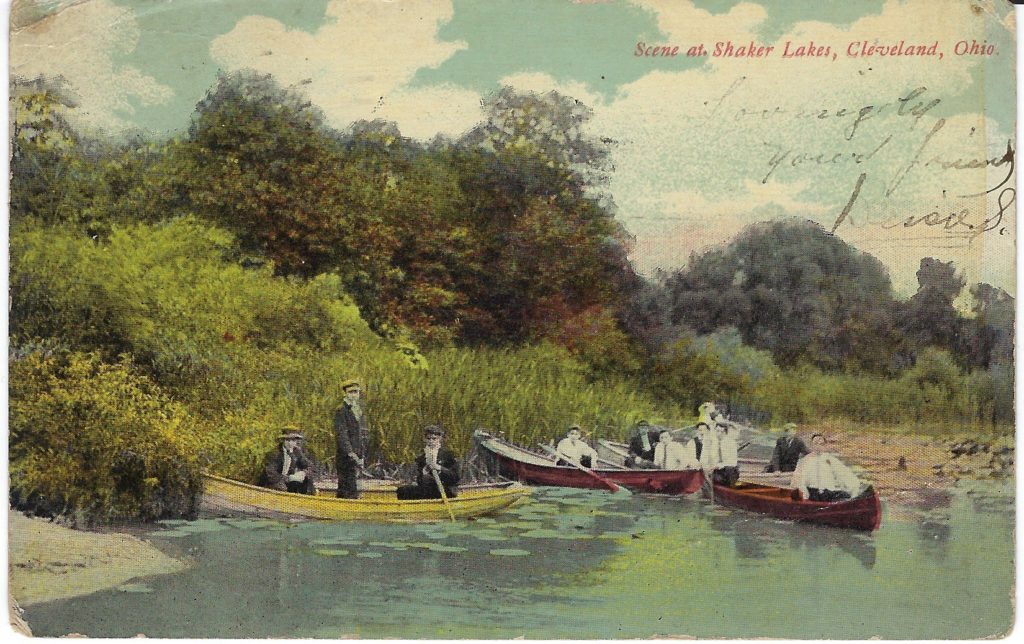

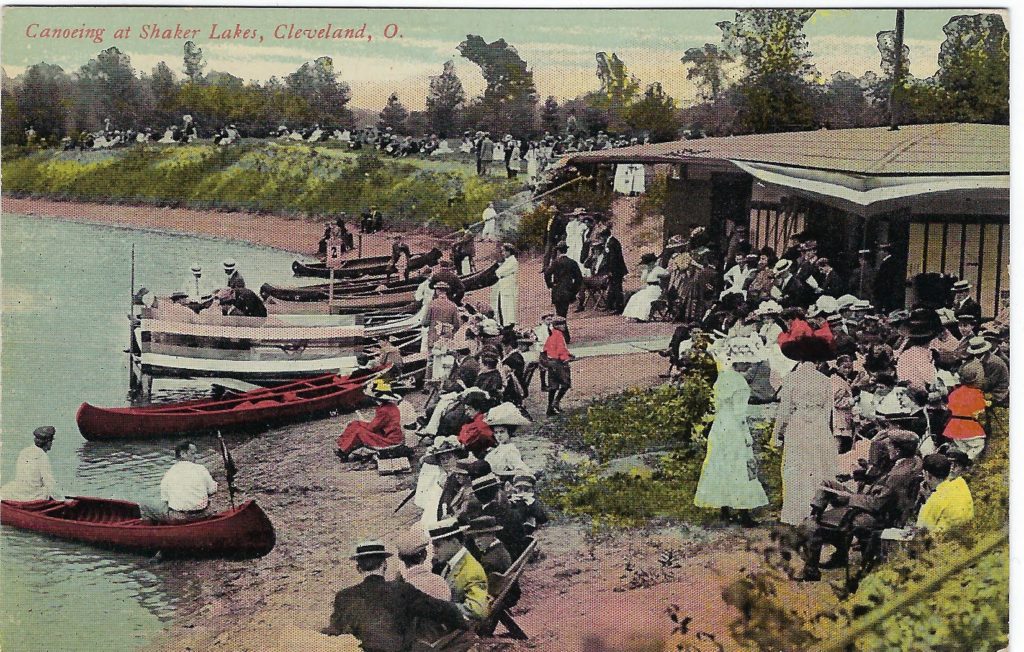

Canoeing was a popular activity on all of the lakes at the turn of the century. A group of boaters was particularly attracted to Lower Lake, the largest inland lake in the vicinity, safer than Lake Erie, and lately accessible by trolley. In 1907 a group of men formed the Shaker Lakes Canoe Club. They built a temporary one-story boathouse at the Canoe Club site, replaced in 1914 with the pictured two-story building. It was leased to the Shaker Lakes Canoe Club for $1 per year from the City of Cleveland. Its members paid $15 a year in membership dues, and did all the building maintenance themselves.

They held regattas with races and jousting matches, often witnessed by 3-5,000 people sitting on the lake’s (then) grassy banks. There were moonlight carnivals and canoeing lessons for Boy Scouts, resulting in Lower Lake having boats on it often. Today Lower Lake is a popular passive recreation park, and we have no intention of building a canoe club and hosting regattas attended by 5000 people!

The Canoe Club was active in the 1960s but would have been destroyed had the Clark and Lee Freeways been built through the Shaker Parklands. As you know, the Freeway Fight saved the Shaker Parklands and our neighborhoods, and resulted in the founding of the Nature Center in Shaker Heights. However, the clubhouse was razed in 1976 after membership dwindled and the governing city (now Shaker Heights) cited the Club repeatedly for code violations including the lack of running water and no sewer hookups.

Friends of Lower Lake and our project began at a meeting convened by Tori Mills in March 2018. Several people interested in volunteering to restore habitat on a regular basis had approached DBWP. We were frustrated to volunteer at a once-a-year service day, only to watch the invasive plants re-sprout with renewed vigor. John Barber and Peggy Spaeth agreed to chair a project involving regular volunteers and Friends of Lower Lake was created.

Our vision is simply that Lower Lake is a habitat rich with native plants that support insects, migrating and resident birds, and people and other mammals. The project fulfills the DBWP mission to “facilitate and support conservation and restoration projects within the watershed” and “increase public engagement and awareness of the watershed.”

Our goal is to remove invasive plants, replace them with appropriate natives, and create an ongoing stewardship plan. Let’s be clear: this is a project with no end. We can’t let nature “take its course.”

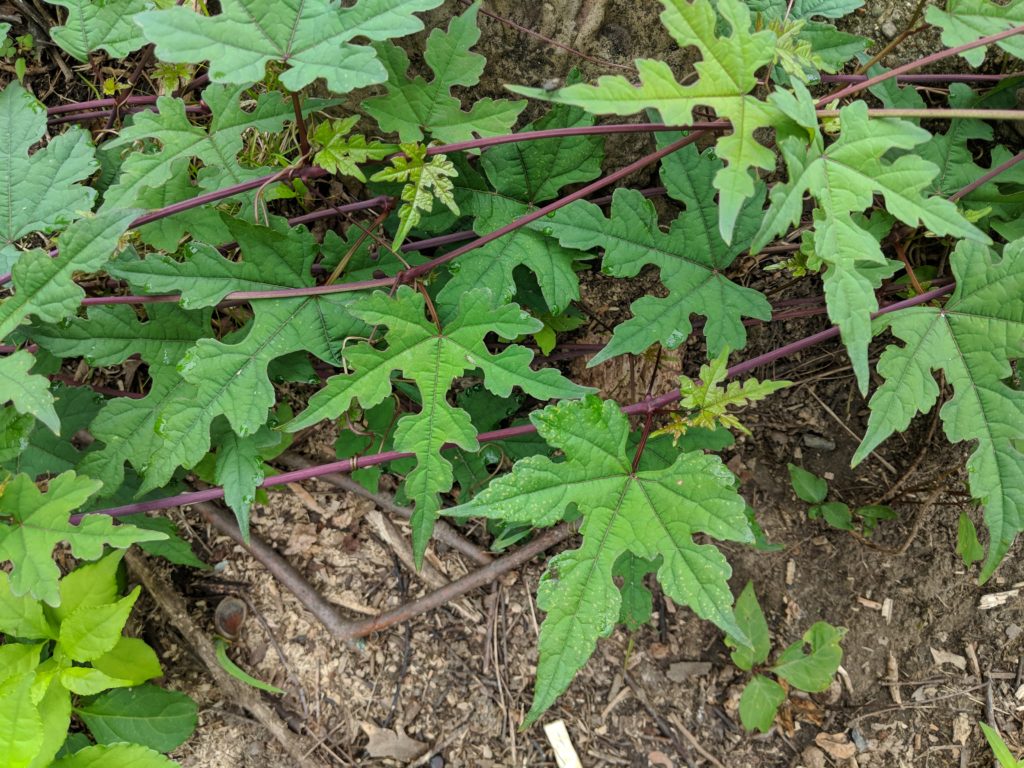

We initially attacked the Canoe Club site because of the huge amount of invasive Porcelain Berry vines dropping seeds into the lake every year. We removed many loads of vines, roots, and seed-infested soil and ended up discovering the foundation.

Doing this work we found 19 species of non-native plants in and around the foundation, all thriving because the site was left “natural.” Invasive plants have few pests to hold them back, and will always out-compete native plants if left alone.

All of the non-native plants we found are on the Ohio banned and invasive plants list and many were first introduced through the nursery trade without realizing the aggressiveness of these species. This includes not only the flowering plants on the site, but also the vines, trees, ivy, and shrubs.

The challenges of our restoration project are complex.

Regional: Here we are removing invasive plants in the middle of the watershed at the Canoe Club site, while upstream Horseshoe Lake has rampant Japanese knotweed and other aggressive invasive species spilling downstream. Fortunately in between we have the Nature Center at Shaker Lakes with Natural Resource Specialist Nick Mikash onboard, and he has been an invaluable ally in our shared project.

Resources: We are a small band of residents who came together to literally dig up decades of invasive trees, shrubs, groundcovers, and vines by hand.

A core group of 8 to 12 peoplehas been working on Sunday mornings since May 20, 2018. A total of 50 have worked at the site, and we welcome people of all ages and abilities. We would love to have crews working around this lake and throughout our community at sites that connect with each other to create a rich unified habitat reflecting our respect and love of the natural world in our community. For the watershed, we need a master plan with a timeline, funding, and resources. This could lead to volunteer crews working under the leadership of a professional natural resources manager.

This has been a truly heartwarming experience to work with people with a shared vision for a healthy environment. We’ve watched eagles, osprey, kingfishers, and other wildlife as we’ve worked. Clearing the foundation has activated the space, with people coming to photograph, talk, do tai chi, tally birds, or just sit. It’s obvious that the Canoe Club was sited at one of the most scenic places on the lake, with friendly prevailing winds pushing canoes west to east back to the launch. Our hope is to create a larger vision for our environment that educates and partners with city government and active residents so that we all take responsibility for a healthy habitat, upstream and downstream.

Please join us! We need more volunteers! Sign up for our newsletter here to stay informed, or email friendsofLowerLake@gmail.com.

about our project

Canoe Club photo album

Plain Dealer pictures 1909-1976

Facebook