by Diana Sette

as previously published in “Permaculture Design: Ecological Restoration #99, online version”

I did not always think of ecosystems as I do now. If you would have asked me ten years ago as a Religious Studies and Literature undergraduate at Drew University what an ecosystem is, I probably would have said it was a marsh with frogs eating dragonflies pollinating daisies photosynthesizing, or maybe a rainforest with monkeys and jaguars and fish and hissing cockroaches. Now, when I hear the word ‘ecosystem,’ I think of something completely different. I imagine a city. I imagine a no-name town off some major highway almost completely paved over with asphalt and maybe an occasional pile of dyed woodchips in a coffin of pavement. Are these not ecosystems too, just extremely degraded to the point where there is barely any sign of life aside from a car driver pumping gas and a courageous dandelion? I also envision communities of people, and the design of a neighborhood. I imagine urban farms, and intergenerational interracial exchanges connecting people and cultures across invisible boundaries. I imagine a family, the trillions of microorganisms living on my hand or in my gut, or the complex web of memories, thoughts, and feelings that comprise a single human being. If an ecosystem is a set of relationships, are we not ourselves and the communities within which we live not also incredibly complex and intricate ecosystems? Unfortunately, with patterns of oppression like racism, classism, sexism, ageism, and ableism, among the other degrading -isms, most of us are living in greatly damaged ecosystems. As the writers of the recent Rights of Nature & Mother Earth put it, we must “recognize that there is no separation between how we treat nature and how we treat ourselves” (1). For the process of ecological restoration to have the greatest impact, we must start work in the area upon which we can have the greatest influence: the ecosystem within. I had no idea when I started on this journey that ecological restoration would bring me here.

Becoming aware of ecosystems

I grew up in a suburb outside of Philadelphia, a town with a strong Colonial history (George Washington’s military headquarters were based there) and a pattern of urban sprawl. Some of the development was a product of white flight, and some of it was the product of a mostly white population climbing the economic class ladder that requires the colonizing of country and moving into a McMansion in order to be ‘successful.’ I remember it being heartbreaking for me as a child to watch the construction of our new home. It was the second phase of a new housing development called Forest Glen. I was entering fourth grade, and I was devastated to move into this new cookie-cutter home with brightly dyed green turf and a tree sapling out front. I was moving away from my community of friends to live where a young forest glen had been decimated in the name of my family. I saw only destruction. Perhaps, this was my first understanding of living within a damaged ecosystem.

The house didn’t feel like home to me. I felt as if I were moving onto ancient burial grounds, having taken over someone or something else’s home with no acknowledgment, let alone sacred reverence, for the place, or wildlife that had lived there before. All the trees were cut, lawns were rolled out, and template houses were erected in assembly-line fashion. I felt at the core of my being how myself, my family, our neighbors, and the developers were responsible for the destruction of this ecosystem. The nature of the development demonstrated a cultural belief that nature has no rights and no value aside from potentially adding to property value.

I was around ten years old at the time of my move. What could I do? All I could think to do was protest by refusing to sleep there the first weekend we moved in. My parents allowed my protest and did their best to make the house welcoming and cozy for me. They were providing for me the best way that they knew how.

In the years following, I watched as more and more old farms and abandoned forests were divided into parcels and sold to developers who quickly paved them and turned them into strip malls. I remember thinking, isn’t there anyone who has lived in this place long enough who will stop this horrible urban sprawl?! By the time I was a teenager, my protests elicited responses like, “this is what progress looks like.” When I finally moved away from that town at the end of my high school years, I felt like a refugee. My homeland had been destroyed. I no longer had a home connected to the land. I left in search of a place to live, because the culture surrounding me seemed one of death and decay despite the glitz.

I went away to college at Drew University in New Jersey and lived in ‘The Earth House.’ There I lived with a Vermonter, and another friend with a connection to that state (2). I visited the rural countryside of Vermont for the first time soon after. I was struck by un-mowed lawns with wildflowers and vibrant local food coops in almost every little town center. My naive suburban upbringing probably contributed to my rose-colored glasses perspective, because everyone I met seemed to know how to cook and garden. People waved to each other passing by on the road, and knew each other’s names at the convenience store. Initially, it was hard to believe that this place was for real.

I learned so much during my time living there. I lived in community while working at Rock Point School, a residential high school for at-risk youth where care for self and care for others were key (3). Later, I spent several years living and working at the Bread and Puppet Theater in a community that drew people from all over the country and world to make radical political puppet theater shows and live on the land (4). We made puppets giant and small from garbage pulled from the waste stream, including cardboard, bottle caps, and the inner tubes of bicycle tires. We insisted that art is for everyone, not something exclusive to art museums or galleries. We ground flour by hand, baked sourdough bread, and raised chickens and veggies to sustain our community. The number of residents staying at the farm ranged from 3 to 200 throughout the year. In the summer, I slept in a decommissioned school bus refurbished as a cozy abode. We heated our old farmhouse through the Vermont winters by wood stove and fed ourselves from the stored harvest.

From five years of living in the Bread and Puppet company full-time, I grasped the concept of the commons. I learned what it takes to live in community through conflict and celebration. I participated in effective grassroots political action, and engaged with the thriving world of microbes. I lived in alignment with the cycles of nature. Foraging through the forests on the 200 acres (80 ha), I learned which mushrooms and plants were edible, and then cooked them together with others in the summer kitchen on rocket stoves. I felt in my heart how a garden without art was only half the story. Having grown up in the suburbs of the mid-Atlantic, I had had no prior understanding of the potential of this type of cultural reality. My inner ecosystem was transformed in a deep way through living in a larger thriving ecosystem overflowing with abundant and resilient relationships.

I never would have guessed that five years and a marriage later, I would move to the post-industrial rust belt of Cleveland, OH where I live currently. Transitioning from the ecosystem of the Northeast Kingdom to Cleveland was a huge cultural shift. Cleveland is the most racially and economically segregated city in America (5). The city has over 12,000 abandoned properties and over 27,000 vacant lots (6). Cleveland is notorious for her Cuyahoga River catching fire 13 times due to egregious pollution. Cleveland is a prime example of a degraded ecosystem. Even though land was plentiful and cheap in Cleveland, growing on formerly abandoned city lots in declining neighborhoods seemed like a very different type of relationship with nature—one potentially lacking in connection.

Surprisingly enough, it was only a month or so after moving to Cleveland where I found myself feeling a deep connection with nature and Mother Earth’s wild spirit. I was at a community potluck at Gather ‘Round Farm, an urban permaculture garden farm in the Near West Side of Cleveland. I had heard of permaculture, although I didn’t know too much about it. Gather ‘Round was built atop a former parking lot. Every path was curvy and intimate alongside raised beds of intercropped heirloom abundance. There were chickens and a little waterway that flowed through the garden. Art made from found objects littered the lot, creating magical alcoves. Folks at the potluck were of all walks of life, coming from different economic, racial, and social strata. Everyone gathered to share community and the organically grown vegetables and other wild edibles in a delicious chili-filled soup. Sitting alongside a brick-lined bonfire and staring up into a star-filled sky, I stopped noticing the cars driving past on the main avenue. I was utterly inspired by the transformation and resiliency of the space. I was encouraged by meeting the all-women volunteer collective who cared for the land. They were empowered with a strong sense of social justice and commitment to community through grassroots action and inclusivity. I knew then I was a permaculturist.

The alignment of social justice, environmental justice, and community came to be my understanding of ecological restoration. I spent the next year observing two vacant lots next to my house on the East side, and getting to know my neighbors in a primarily African-American neighborhood before cooperatively creating Possibilitarian Garden, an urban permaculture garden and community orchard grounded in racial equity, food, and social and environmental justice. Possibilitarian Urban Regenerative Community Homestead, or PURCH, is the name we use to include the cooperative living house and community workshop space alongside the garden on two formerly vacant lots. Permaculture design presents solutions to the problem of ecological degradation, and now we have the opportunity to co-create working ecological models. Who knew I’d be here now?

What is ecology anyway?

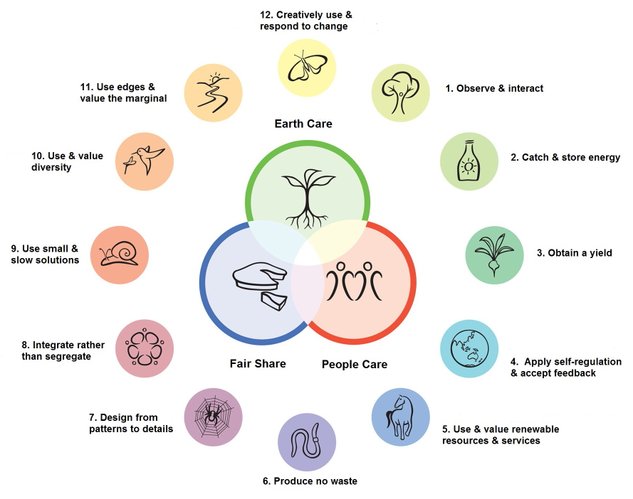

Permaculture is grounded in ecological theory. Audrey Tomera in Understanding Basic Ecological Concepts (7) defines ecology as “the science that deals with the specific interactions (relationships) that exist between organisms and their living and nonliving environment.” Therefore, permaculture is simply the observing of and designing for optimal relationships between organisms and their living and nonliving environment—permaculture is ecological design.

Bill Mollison and David Holmgren, permaculture’s founders, were both trained ecologists. Holmgren dedicated his 2002 book, Permaculture: Principles and Pathways beyond Sustainability (8) to Eugene Odum, one of the founding scholars of ecology who brought ecological thinking to the mainstream with his book Fundamentals of Ecology (9). Interestingly, there are conservation ecologists, urban ecologists (10), deep ecologists, ecosystem ecologists, civic ecologists (11), human ecologists, evolutionary ecologists, schoolyard ecologists (12), microbial ecologists (13), and even ecosystems ecologists! Each ecology field is based on the study of relationships—the fields differ in the lenses with which they study those relationships (14).

Older ecological design studies tend to not include humans, never mind that most ecologists will agree that humans now have the largest impact on every ecosystem on this planet. Urban and social permaculture is the cutting edge for research and practice in ecological systems, as more the half the world’s population lives in urban environments. Within the permaculture movement, more buzz is growing around urban and social ecosystems. Recent books like Hemenway’s The Permaculture City: Regenerative Design for Urban, Suburban and Town Resilience (15) contribute to the increasing study of urban ecologies.

Assessing ecosystem health

Analyzing separate ecosystem elements to assess ecosystem impact (and arguably for other purposes as well as discussed below) is where I see the greatest divergence between colonized and indigenous ecological thinking. For example, in 2011, the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (16) broke down the ecosystem services into four main categories: provisioning, regulating, cultural, and supporting services (17). The direct and indirect contributions of ecosystems listed are extensive, ranging from providing food, shelter, and clean water, to creating a sense of place and spiritual experience.

Identifying ecosystem services is one way to assess ecosystems. It is important to note, however, that to engage with the ‘ecosystem services’ assessment tool is to work in opposition to indigenous people’s ‘Rights of Nature,’ which demands “the rejection of all market-based mechanisms that allow the quantification and commodification of Earth’s natural processes, rebranded as ‘ecosystem services’ ” (1).

I respect and honor this perspective, as I have felt how assessing ‘ecosystem services’ using monetary value is the first step to commodifying something with deeper qualitative and priceless value. I remember the first time I saw ‘ecosystem services’ signified by an old centennial oak. Hanging on a sign pole, a big tag marked what the tree’s monetary worth was. It communicated to me that the tree was paying its due, and therefore was allowed to stick around for a little bit longer until humans decided it wasn’t worth it anymore. Marking ecosystem services in this way promotes and protects current laws that prescribe what Rights of Nature describes as “the ownership of ecosystems and other aspects of the natural world…, upholding the control and dominance of humans over nature” (18).

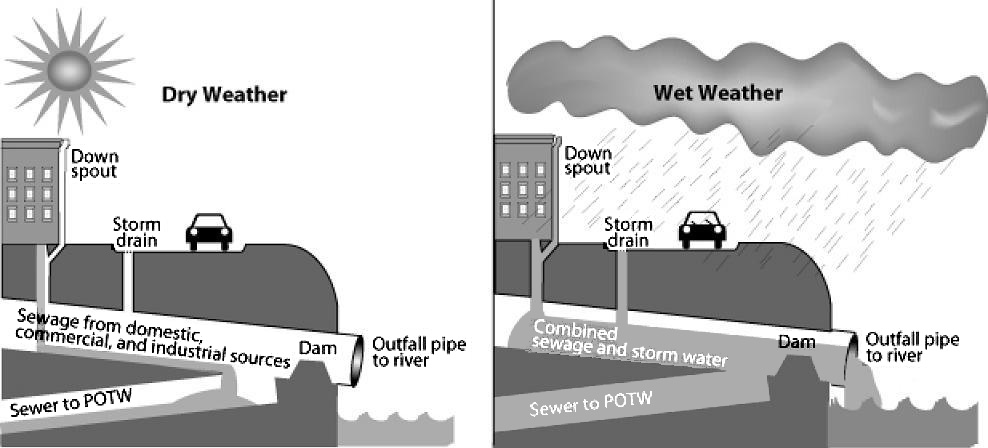

While modern societies have clearly lost touch with indigenous wisdom regarding ecosystem health and needs, it can also be useful and necessary (at least for the time being during this Great Transition) for ecological designers to use ecosystem assessment tools as a gateway to observing and understanding ecosystems better. Tools like the EPA National Stormwater Calculator (19), National Tree Benefit Calculator (20), climate and weather patterns, soil quality tests, and other ecosystem services calculators and measurement tools (21) track non-human systems. Demographic surveys and cultural histories of a place provide foundational information for design considerations as well. Having a grasp of cultural, economic, and social patterns for your design site can be the keystone for truly resilient ecological restoration (22).

Moving forward

The notion of owning ecosystems brings to light several of permaculture designers’ greatest risks in ecological design. If our cultural heritage is non-indigenous, we most likely carry within our personal ecosystem patterns of colonization, oppression, and subjugation. We must work cooperatively, and engage and include various diverse voices of different demographic (and species) background in the design process (23). Restorative ecological design considerations can all be identified as issues of social and environmental justice, and we must work to understand them as such if we hope to successfully support Nature’s ability to restore her ecological systems.

This observation brings us full circle. We must start with our inner ecosystem, observing our thoughts, our patterns, and the ways our body, mind, and soul interacts with itself. Whatever spirit with which we communicate will be what we transfer to any other ecosystem, including our family, organization, neighborhood, community, farm, or forest. We must bring awareness to unconscious biases, privileges, and personal cultural beliefs in order to be able to understand how we carry them forward as designers and how that impacts our ability to co-create resilient ecological restoration.

To that end, the global climate is changing fast, and new patterns are emerging and transforming constantly, so we must trust our direct and attentive observations. Do not overlook the force of nonliving factors, as living things are in constant interaction with them. Honor that every being, living or not, has a special ecological niche that only it can fill, and whether you understand it or not, there is a reason they need to do what they do currently. Allow that to direct your interactions and engagement with bumblebees, real estate agents, drug dealers, microorganisms, artists, fences, trees and rocks. Be inclusive. Remain curious. Value complexity. Work the edge, and work to understand best you can, because even though it may be hard to see the value of some element, keep all the pieces- we will need them all as we move forward to restore our damaged and degraded ecosystems. The principles and ethics are a road map and a check and balance; use them. Take action. Listen for feedback. Respond with change. And when practicing ecological restoration, remember the words of indigenous artist and activist Lila Mills who said, “If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.” ∆

Diana Sette is a Certified Permaculture Teacher and Designer working primarily in Cleveland, OH, after almost a decade of growing in the Green Mountains of Vermont. She serves on the Board of The Hummingbird Project (hummingbirdproject.org) and Green Triangle (greentriangle.org), two permaculture-based non-profits working locally and abroad. Much of her work in social and urban permaculture experimentation is centered at Possibilitarian Urban Regenerative Community Homestead (PURCH) in Cleveland (Facebook: Possibilitarian Garden). Diana currently works for Cleveland Botanical Garden as the Youth Manager of Green Corps, its 20-year-old urban agriculture work-study program for inner-city teens.

[Editor’s note: We inadvertently misspelled the author’s first name in PcD #98. We regret the error.]

Notes

1. Biggs, Shannon & Tom B.K. Goldtooth, eds. Rights of Nature & Mother Earth: Sowing Seeds of Resistance, Love and Change. therightsofnature.org/tag/rights-of-mother-earth/ Nov 29, 2015.

2. One friend, Graham Unangst-Rufenacht, is now an herbalist, edible landscaper, and owner of Robinson Hill Beef, a grass-fed cattle business you can find on Facebook at www.facebook.com/RobinsonHillBeef/. Another friend, Sarah Corrigan, later went on to co-found ROOTs—Reclaiming Our Origins in Traditional Skills School—in VT. rootsvt.com

3. Rock Point School in Burlington, VT, is now one of the leading providers of renewable energy for the city of Burlington with the construction of an extensive solar panel orchard. www.rockpointschool.org

4. Bread & Puppet Theater. Breadandpuppet.org

5. Frohlich, Thomas C. & Alexander Kent. “America’s Most Segregated Cities” 24/7 Wall St. 247wallst.com/special-report/2015/08/19/americas-most-segregated-cities/4/ August 19, 2015.

6. A total of 12,179 vacant structures equates to 8% of the city’s parcels; 27,774 vacant lots is 17% of the city. 2015 Citywide parcel survey of Cleveland. www.wrlandconservancy.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/WRLC_Loveland_Cleveland_Survey_Report_20151121.pdf Nov 20, 2015.

7. Tomera, Audrey N. & A. Tomera. Understanding Basic Ecological Concepts. Portland, ME: J Weston Walch (2002).

8. Holmgren, David. Permaculture: Principles & Pathways beyond Sustainability. Hepburn, Victoria: Holmgren Design Services (2002).

9. Odum, Eugene. Fundamentals of Ecology. Philadelphia: Saunders (1953).

10. Niemelä, Jari, ed. Urban Ecology: Patterns, Processes, and Applications. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press (2011); Mark McDonnell, Amy K. Hahs, & Jürgen Breuste, eds. Ecology of Cities & Towns: A Comparative Approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press (2009); “Nature of Cities,” a collective blog on cities as socio-ecological spaces: www.thenatureofcities.com.

11. Krasny, Marianne E. & Keith Tidball. Civic Ecology: Adaptation and Transformation from the Ground Up. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press (2015).

12. Dank, Sharon Gamson. Asphalt to Ecosystems: Design Ideas for Schoolyard Transformation. New York: New Village Press (2010).

13. Antonio Gonzalez, Jose C Clemente, Ashley Shade, Jessica L Metcalf, Sejin Song, Bharath Prithiviraj, Brent E Palmer, & Rob Knight. “Our microbial selves: what ecology can teach us.” EMBO Reports 12: 775-784. embor.embopress.org/content/12/8/775 (2011).

14. Many ecological theories have been developed, although many more are needed, as the world is quickly urbanizing, and patterns are changing and transforming. Some ecological theories include: island biogeography theory, metapopulation dynamics, human ecology model, etc. Applying these theories in an urban versus rural context may demonstrate variation in behaviors.

15. Hemenway, Toby. The Permaculture City. White River Jct., VT: Chelsea Green (2015).

16. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment: www.millenniumassessment.org

17. More specific definitions of ecosystem services included at The Economics of Ecosystems & Biodiversity (TEEB) website: www.teebweb.org/resources/ecosystem-services/

18. RoNME

19. www2.epa.gov/water-research/national-stormwater-calculator

20. www.treebenefits.com/calculator/

21. California ReLeaf’s website includes additional ecosystem service calculators and measurement tools: californiareleaf.org/resources/calculators-and-measurement-tools/

22. The City Repair Project based in Portland, OR. www.cityrepair.org/ and Cleveland, OH www.neighborhoodgrants.org/city-repair-cle-closes-the-season/ are interesting examples of community permaculture design working towards ecological restoration.

23. For a hefty start to understanding social and cultural patterns, see the in-depth articulation of social and architectural patterns in the following books: Alexander, Christopher, M. Silverstein, & S. Ishikawa. A Pattern Language. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press (1977); Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House (1961); Schuler, Doug. Liberating Voices: A Pattern Language for Communication Revolution. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press (2008) by Doug Schuler. Other ecology resources include these journals: Ecology, Ecology & Society, Human Ecology: An Interdisciplinary Journal, Human Ecology Review, and the Journal of Political Ecology.

http://permaculturedesignmagazine.com/

Daniel and Rosemary checking out an aquaponic system in action at Seedfolk City Farm (

Daniel and Rosemary checking out an aquaponic system in action at Seedfolk City Farm (