by Tom Gibson

(This is the inaugural installment of what we at Gardenopolis Cleveland hope will become an ongoing series. Have you read something in a gardening book or blog or article that made you want to try something new? How did it work out for you? We’re looking for short, pithy articles not only from editors, but from you, the reader.)

Garden Experiment #1: Sorghum-Sudan Grass

One of the garden “stars” in Michael Phillips’ book Mycorrhizal Planet is Sorghum-Sudan grass (sorghum sudanese). This annual grows up to 12 feet tall very rapidly, especially in hot weather, thus creating lots of compostable biomass. But it has two other special virtues: 1) Its roots can provide habitat for up to 50 species of mycorrhizal fungi. And 2) when mowed, the plant responds by expanding its root mass, sometimes by a factor of two. That means lots of carbon for microflora to feast on during the next growing season.

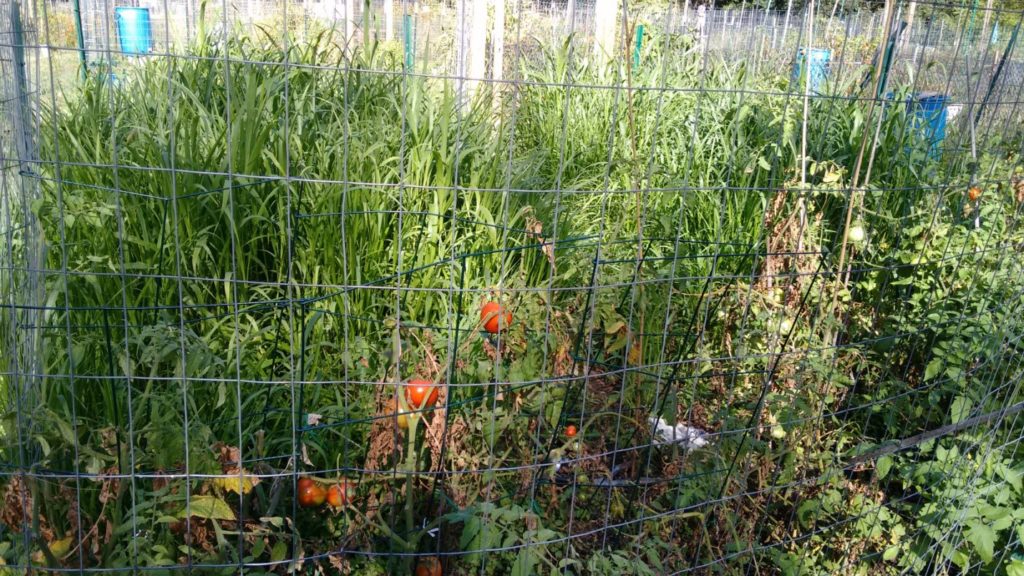

If ever soil needed more carbon, it was the garden plot I inherited at the Oxford Community Garden in Cleveland Heights. Light tan in color, it was clearly more dirt than soil. Weeds like thistle (that thrive in calcium-and phosphorous-deficient soil) loved it. Although I reserved one strip of my plot for an attempt at tomatoes (aided by some calcium sulfate and worm castings), I seeded the rest in July with sorghum-sudan grass along with a multi-species, mycorrhizal-based fertilizer with the brand name of Dr. Earth. I bought the latter at Home Depot, something that would have been impossible just a few years ago before mycorrhizal additives started to go mainstream.

The seed (5 lbs. that I bought online at seedranch.com for just $15) was easy to sow, though it required coverage from bird-proof netting. (Flocks of birds flew away as I approached the garden after my initial broadcast planting!) The seed germinated right away and quickly dominated the plot.

Then, in early October, I trimmed the grass with hedge clippers. The cut grass should be no less than six inches high, Phillips says, for the best post-trimming root expansion. Next spring is when I’ll take a mulching mower to the process. Then I plan to plant right into the plant-stubbled soil. I’ll let you know what results.

Garden Experiment #2: Roasted Stinging Nettle Seeds

This idea comes from the far corners of the Web, where hairy counterculturists congregate. (e.g. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z7TJwh5nu9Y and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rD4kDo0Z7Y4). These videos drew me in because stinging nettle has become one of my favorite garden vegetables. It’s great with garlic and eggs for breakfast and in evening meal main courses such as stinging nettle lasagna. And, as permaculturists know, stinging nettle offers twice the nutritional value of even vitamin-and-mineral-rich mainstream vegetables such as spinach. (I tell my permaculture classes that nettles have developed a sting for the same reason that banks install alarms: to protect valuables stored inside! Fortunately, deer don’t wear gloves or know how to steam the leaves to neutralize the formic acid sting, so stinging nettle offers the added benefit of being herbivore-free!)

Stinging nettle seed is just as rich in nutrients as the leaves. This year, with regular rains extending into July, my stinging nettle seed crop was exceptionally robust. How much effort, I asked myself, would it take to collect the seed and was it worth the effort?

I was feeling pressed for time, so, as a test, I just cut the six longest stalks and dumped them top first into a refuse bag. There they sat drying (until I remembered them!) for almost two months. Then I cut off the little bunches of seed pods and pressed them into a colander. Voila! Tiny black seeds emerged on the other side. We then roasted them with a little salt and oil. The result: nutty and crunchy.

Critically, the roasted nettle seeds pass the all-important “wife test.” They added a nice crunchy texture to the rice and veggie lunch we prepared. We thought, however, they might stand out best on simpler dishes such as scrambled eggs or plain rice.

In terms of future garden productivity, the newly-discovered edibility of stinging nettle seed extends the harvest season of what has become, for us, a staple crop. The leaves are at their best from May through June, but become less digestible when plants start to flower in July. (One of the visual pleasures of a breezy July day is to watch wind-borne clouds of nettle pollen drift past their neighbors.) Now we can harvest seed in quantity, roast it, and enjoy it during the winter months.