by Tom Gibson

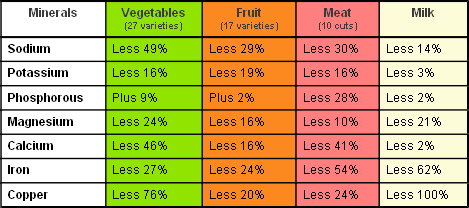

It is common knowledge, both among scientists and educated consumers, that food is less nutritious than it used to be. Here’s a chart that shows how great mineral loss was between 1950 and 1999:

Later studies confirm that the situation has only worsened. One familiar culprit is the need by our modern industrial food system to require “efficiencies:”synthetic fertilizers, plant breeds that withstand long distance shipping, feed-lot-fattened meat, etc. Less familiar, is humanities’ fatal dietary flaw, its sweet tooth that can’t resist anything sugary. As Jo Robinson relates in her great book, Eating on the Wild Side, even blueberries, those alleged carriers of anti-cancer, anti-everything-bad nutrition, have lost much of their natural potency through over-breeding to accommodate humanity’s too-sweet palates. The more sour the blueberries, the better they are for you. (Robinson recommends the semi-wild “Rubel” variety. Sour, but good for you.

Two recent developments that shed new light on the nutrition issue, however, caught my eye. First, the bad news: Declining nutritive value may well also be a consequence of the general rise in CO₂ concentration in Earth’s atmosphere. Carbon dioxide not only causes global warming, it also speeds photosynthesis and, with it, plant metabolism. Multiple scientific studies now show that this process weakens uptake of vital mineral nutrients like zinc. The most convincing evidence of causality is that even non-crops like goldenrod, samples of which have been collected and preserved since the 19th Century, have also lost nutritional content. The only variable, apparently, affecting goldenrod has been rising CO₂ concentration.

Please Don’t Eat the Goldenrod

Please Don’t Eat the Goldenrod

This is especially depressing news since it identifies a variable that impossible for individuals to correct on their own. Even if you work to balance micro-nutrients in your own garden, global conditions will always be tugging in the opposite direction.

(For a well-reported article accessible to lay readers, see http://www.politico.com/agenda/story/2017/09/13/soil-health-agriculture-trend-usda-000513)

But don’t give up hope. The second item I noticed (the good news) gives us at least some chance to take better nutrition, quite literally, into our own hands. It’s a prospective I-Phone app—a Bionutrient Meter– that will allow you to perform an instant spectroscopic analysis on fruits and vegetables in grocery bins. Does that spinach at Whole Foods contain the iron you want it to? Or does the farmer’s market offering outperform it? Just point and click. And the larger question: Will a small army of consumers demanding better nutrition put enough pressure on suppliers to change their standards?

An organization I greatly respect, the Bionutrient Farmers Association**, will unveil a prototype Bionutrient Meter this fall. In this podcast, Dan Kittredge, gives more detail. ((https://soundcloud.com/wpkn895/digging-in-the-dirt-37-dan-kittredgeexecutive-dir-bionutrient-food-assoc/ ) His hope is that an affordable handheld device will be available to consumers a year-and-a-half from now.

*I’m ignoring here the far worse role played by manufacturers of highly processed food scientifically formulated to create junk food addictions among naïve populations. For a truly depressing, but well-reported article that includes a quote from Cleveland’s (and Switzerland’s) own Nestle Corporation, see https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/09/16/health/brazil-obesity-nestle.html?_r=0

** (bionutrient.org. Note that “bionutrient” is not plural. Adding an “s” will take you to the wrong website.)

Nutrient News (You Can Use) II

It may be news to you that many good elderberry recipes exist. Although American use of these tiny, astringent black fruits is pretty much limited to elderberry jelly and elderberry wine, European cooks take them much more seriously. This is a good thing, since elderberries are off the charts in their nutritional value—double, for example, the anti-oxidant power of even the most nutritious blueberry. (Sorry, Rubel blueberries! See above.)

Sambucus Nigra, a European variety, though we also use the North American Sambucus Canadensis*

Sambucus Nigra, a European variety, though we also use the North American Sambucus Canadensis*

The best sources for many of these recipes are online and often not in English. But don’t let that stop you! All you have to do is look up the foreign word for the fruit you contemplate cooking, enter that and the foreign word for recipe, and you’ll get an extraordinary variety of good ideas. Just right-click on any given recipe, and it will appear in English. It’s really that simple, with only a mental barrier to stop you.

In the case of elderberry, several years ago I looked up its German translation, “Holunder” and the German word for recipe, “Rezept.” The resulting search led to a fruit compote that has become a family favorite. The genius of this particular dish is that it takes the “bass note” astringency of elderberries and lemon peel and matches them with the treble notes of sweeter pears and plums. The result is an unusual symphony of fruit flavor that we like on ice cream and on cereal.

Here’s a free adaptation of the recipe:

8 firm pears

1 liter water

1 lemon, juice and zest

1.5 Kg of Italian prune plums, de-stoned

1 Kg of elderberries

400 g sugar (yes, the best flavor requires some additional refined sugar sweetness!)

Core the pears and chop into bite-sized chunks, add water and lemon zest, then cook until almost tender. Add the plum halves, elderberries, sugar, and lemon juice and bring to a boil. Reduce to a simmer for 30 minutes. We pour into jelly jars and freeze.

*The elderberry bush is an especially useful permaculture shrub since it allows easy “function stacking”—the permaculture term for getting multiple benefits out of the same piece of land. In our case, we grow tasty king stropharia mushrooms in wood chips in the shaded soil beneath the elderberry bushes, which, in turn, benefit from the decomposed-wood-chip soil. We also grow groundnuts, a frequently-found-in-nature companion plant to elderberries. The groundnuts vines curl up the elderberry bush branches, even as its roots fix nitrogen and feed the plants around them. Three foods in one patch of ground, ever better soil, more nitrogen, plus a privacy hedge between us and our neighbors. Now that’s function stacking! (Though it’s taken more time than I thought it would.)