by Tom Gibson

Regular readers of this blog will have gathered that our personal Cleveland Heights home landscape can be fairly characterized as “bold:” Native plants with no grass in front and permaculture Food Forest plantings in back. Some of the latter are pretty exotic—skirret , goji berries, even the oft- discussed native pawpaws . But in one respect, we have kept the homestead “timid:” no mushroom cultivation.

We’ve just read too many stories of mushroom “experts” making fatal or near fatal (requiring kidney or liver transplants) mistakes. So we have carefully avoided either sampling the mushrooms that regularly emerge from our heavily shaded, oak-hickory landscape and have even remained reluctant to spread the spawn of mushrooms deemed safe.

That’s changed. It all began slowly. A Food Forest seminar several years ago at Holden Arboretum left us with one sample inoculated shitake log.

(When the shitakes finally emerged, we ate them and survived!) Then last fall I inoculated a patch of King Stropharia spawn underneath a stand of elderberries. This fall the distinctive wine-colored mushrooms popped up.

We ate them and survived again!

Now, though, we’re moving much faster. The proximate cause: A course I took this fall at Ohio State University (“Mycelial Lectures”) that provided a broad overview of fungi and their natural role. As part of that course, I combed both scientific and permaculture literature to write a research paper on “Maximizing Positive Fungal Power in the Food Forest.”

Here’s what we now plan:

- Expansion of King Stropharia plantings to front and back yards and as companion plantings to vegetables in our community garden plot.

- Inoculation of nameko mushroom spawn to as many fresh cherry logs as possible (a dozen?) to key companion planting locations in our Food Forest.

- Inoculation of at least a dozen logs with shitake spawn.

We also plan to harvest maitake or “hen-in-the-woods” mushrooms which have been growing wild under our very noses for years without our knowing what they were.

At this point the mushroom-savvy reader will no doubt want to place a hand on her forehead and shake her head in dismay. What to us looked like ugly gray-brown eruptions on oak stumps are, in fact, widely sought-after delicacies!

Here’s what I learned from the course and elsewhere that has transformed my thinking:

- Of the 17 mushroom poisoning deaths reported annually on average in the U.S., 16 are due to the Angel of Death (amanita bisporigera) mushroom, which in its earliest stage looks like the edible porcini.

While other poisonous species can cause considerable damage, they tend to look quite different than the ones I plan to eat. (Even the nameko,

While other poisonous species can cause considerable damage, they tend to look quite different than the ones I plan to eat. (Even the nameko,  which the very unwary might confuse with galerina marginata,

which the very unwary might confuse with galerina marginata,  is distinguished by clear identification points. Or at least that’s what the literature says. Hmmmm… After looking at these pictures, I’m going to have study this further!)

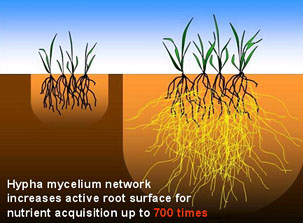

is distinguished by clear identification points. Or at least that’s what the literature says. Hmmmm… After looking at these pictures, I’m going to have study this further!) - Fungal variety contributes to plant variety and productivity. (The reverse probably works, too, with plant variety contributing to fungal variety. But that point is, surprisingly, subject to hot scientific debate.) Most garden fungi are invisible to the naked eye, but are essential to the survival of most plants. They have co-evolved over millions of years to provide auxiliary root systems with special capabilities for scavenging hard-to-access elements such as phosphorous. This much I already knew.

But what I learned in the course was how multiple combinations of fungal strains can lead to greater plant productivity. Six fungal strains may contribute more together to a given plant than any one strain alone. Moreover, plants select which fungi do the best job of providing them nutrients and reward them accordingly with more sugars. (Lots of chemical intelligence in the soil that we’re just beginning to understand!)

- Study of fungal/plant interactions still leaves enormous gaps. There is a tremendous amount no one knows for sure. But intriguing companion planting anecdotes abound. David and Kristin Sewak, the market gardeners who wrote the mushroom neophyte’s book Mycelial Mayhem, say, for example, that King Stropharia mushrooms thrive in the shade of tomato plants and stop late season tomato blight. I plan to copy their method in my community garden plot. And the mushroom blog Radical Mycology reports that nameko mushrooms have a near miraculous effect on both growth and fruiting of neighboring woody perennials . Thus my interest in namekos for my own Food Forest.

- The number one predictor of fungal species variety worldwide is precipitation. The lesson for the gardener is to never ever, ever let your landscape dry out: swales, mulch, watering—whatever it takes.

You experienced gardeners know that already, of course, but understanding one of the key “whys” reinforces motivation.

You experienced gardeners know that already, of course, but understanding one of the key “whys” reinforces motivation.

- The best way to ensure the productivity of most edible mushrooms—i.e., in the phylum known as basidiomycota, including the mushrooms you see pictured in this article and the puffballs below—is to have an adequate supply of calcium in the soil.

(I’m not sure yet what “adequate” entails, but I’ve been adding gypsum or calcium sulfate to support fruit set in my mini-orchard anyway, so I’m reassured.)

(I’m not sure yet what “adequate” entails, but I’ve been adding gypsum or calcium sulfate to support fruit set in my mini-orchard anyway, so I’m reassured.)

Longer term:

If fungal variety is so great for gardens, why not find a way to introduce more? Here systemic knowledge is also lacking. Once established, many fungi are powerfully resistant to colonization by competitors. Yet some fungi valuable to humans and gardens alike, like King Stropharia, are known to spread aggressively. Wouldn’t it be great to have the tools to perform a nuanced analysis of existing fungal populations and an equally nuanced set of guidelines for introducing sustainable populations of beneficial fungi to the soil? Maybe in 10-20 years….

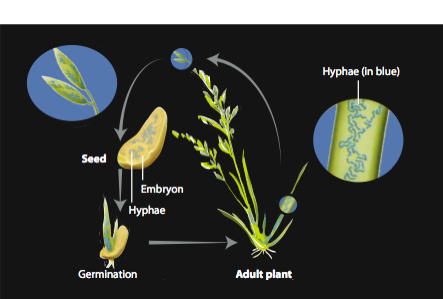

And what about endophytic fungi? This is a class of fungi about which I previously knew nothing. These are microscopic fungi that live within plant tissues, sometimes mutualistically, not as parasites.  Scientists have known about these fungi for over a century, but new tools for computerized genetic analysis have revealed their overwhelming numbers and variety. Many actually help their plant hosts either grow or ward off disease. Most plants acquire these fungi “horizontally,” the same way we catch flu. Studies have shown that suburban trees harbor fewer of these potentially valuable endophytes than the same tree species growing in native forests. Could we make up that deficit in our gardens with foliar sprays of beneficial fungi? Once again, maybe in 10 to 20 years.

Scientists have known about these fungi for over a century, but new tools for computerized genetic analysis have revealed their overwhelming numbers and variety. Many actually help their plant hosts either grow or ward off disease. Most plants acquire these fungi “horizontally,” the same way we catch flu. Studies have shown that suburban trees harbor fewer of these potentially valuable endophytes than the same tree species growing in native forests. Could we make up that deficit in our gardens with foliar sprays of beneficial fungi? Once again, maybe in 10 to 20 years.

Assuming that I continue to avoid eating toxic mushrooms, I’ll let you know then!

Great article Tom! I’ll have to look into this when I add the second permaculture bed. Hopefully this spring!

Great topic, excellent focus on the benefits of fungi in the garden! A helpful site for mushroom identification for northeastern USA (we share many species with New England): http://mushroom-collecting.com There are unique ID features for every species, such as gills/no gills, color when bruised, odors, and so on. Not advocating wild-collecting for all, but mushroom ID is a wonderful activity when hiking!

Tom,

I learned a lot from reading this. Not sure that I understand much of it or can use it. The woman who did a species census for us took photos of mushrooms in our oak forests. maybe my Tom can send you a copy if you like.

Eva