by Tom Gibson

My property doesn’t have a lawn like this. It’s all native plants and/or permaculture Food Forest.

The crowd I hang out with doesn’t much like lawns, either. Why grow grass, my Food-Not-Lawns friends say, when you can raise and harvest your own vegetables and do your small bit toward saving the planet?

This attitude can fall a bit on the humorless, rigid side, of course. Where are young children (e.g. my grandchildren) supposed to play catch or turn cartwheels? Certainly not in the potato patch.

My views on lawns softened still further this spring when I had the good fortune to take an Ohio State University course in “Soil and Climate Change” with Prof. Rattan Lal.

Dr. Lal, winner of multiple awards, is one of this state’s great treasures—a world leader in soil science, a driving force behind the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (the organization that shared the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize with Al Gore); incoming president of the International Soil Association; and a prime source of the science behind the new Paris Climate initiative to transfer carbon out of the atmosphere into agricultural soils. Dr. Lal’s co-teacher of this course, Dr. Berry Lyons, Director of OSU’s School of Earth Sciences, (no slouch, either), put the climate in geophysical perspective.

The course is required for all graduate students in OSU’s School of Environment and Natural Resources.

So, wow, what an intellectual adventure! (and under Program 60, I could take the course for free!)

Our main task as students was to make class presentations that related our current scientific research into climate change. Since I’m not a science graduate student—far from it!—I chose, as best I could, to evaluate other people’s research into the question of carbon capture by suburban landscapes. Plants, of course, breathe in carbon dioxide (CO₂), turn it into sugars, and send those sugars into the soil via root growth and microbial interaction. And that holds just as true for home landscapes as it does for rain forests.

Has research advanced enough, I asked, so that we could easily estimate how much carbon each home landscape—grass, trees, perennials, etc.— captured from the atmosphere and “sequestered” (the technical term) carbon in the soil? What if homeowners could erect a small sign in their front yards that said, “This landscape sequesters 1 ton of carbon annually?”

In other words, could homeowners consciously start measuring and saving carbon and make their own individual contribution to reducing Greenhouse Gas-induced global warming? There’s plenty of social pressure, especially in “neatnik” suburban neighborhoods, to keep every blade of grass trimmed. How about creating an alternative social pressure that’s aimed at saving the planet?

WARNING: TO SKIP THE “SCIENCE” SECTION YOU CAN SCROLL DOWN TO THE SECTION BELOW ON “BOTTOM LINE FOR PLANET-SAVING LAWNCARE.”

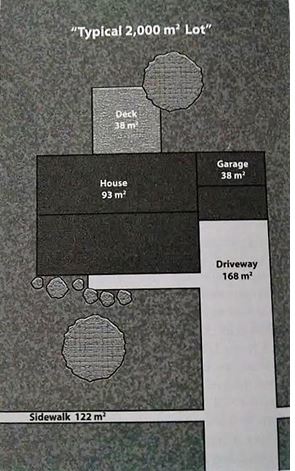

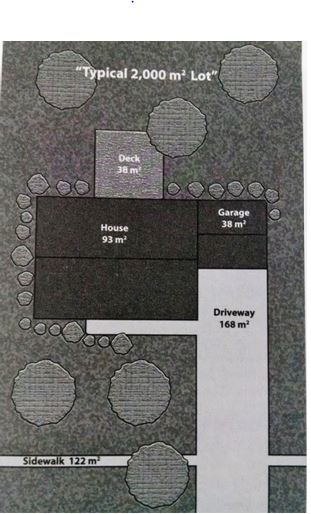

Actually, research into home landscape carbon capture and emission is extensive. For example, a 2012 study compared a landscape with grass, two trees and six bushes….

…..with a landscape with less lawn, but 4 more trees and 17 more bushes…

The landscape with more trees and bushes (and, of course, deeper carbon-filled roots) sequesters more carbon, but the grass roots sequester carbon, too. According to this study, the latter landscape could sequester up to a quarter ton of carbon annually.

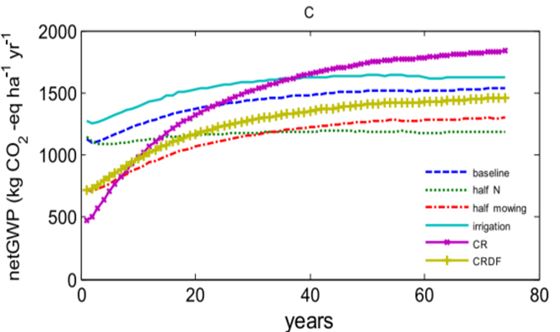

But there are tradeoffs, too, which other studies make clearer. What if the homeowner fertilizes the grass with artificial fertilizer? And how about the Greenhouse Gas effect of power mowing with gasoline?

A 2013 study of home landscapes in Nashville shows some of the impact:

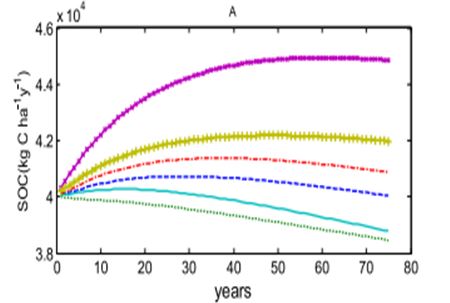

1.Fertilization of grass creates lots more soil organic carbon (SOC):

2. But at the cost of lots fertilizer-induced emissions of nitrous oxide (N₂0), a Greenhouse Gas with almost 300 times the potency of carbon dioxide (CO₂)

3. Add in the effects of gasoline-powered mowers and you can see that conventional lawns emit more Greenhouse Gases (vertical axis, called CO₂ equivalents) than they sequester carbon and have a net positive Global Warming Potential (GWP):

So where’s the problem and what can we do about it?

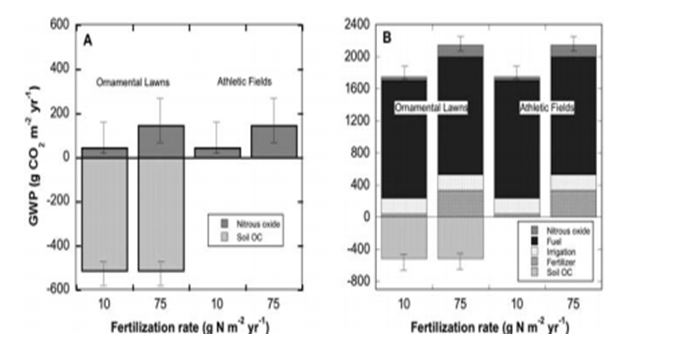

A final study sheds some light (and hope). It looks at ornamental lawncare in San Diego and reveals the main culprit: gasoline-powered mowing. Look for the heavy black section in the right box. That’s how much fuel contributes to Global Warming Potential. Without gasoline-powered mowing, lawns would capture more carbon than they and their fertilization emit.

For all the research I located, I still felt I lacked complete information. I found no similar studies that addressed organic lawncare—compost instead of artificial fertilizer, aeration that increases root growth and carbon capture, etc. Nor could I find studies that measured carbon capture in temperate food forest systems—the kind we permaculturists might construct. In short, nothing that could be reduced to a simple sign that says “This Landscape Sequesters X Amount of Carbon.” (If any reader knows of such studies, please let me know.)

“BOTTOM LINE FOR PLANET-SAVING LAWN AND LANDSCAPE CARE.”

What does science tell you about how maintain your landscape in the most planet responsible way? Mainly, at this point, generalities:

1.Leave your lawn clippings in your grass and make them the sole source of fertilization. (If you want more fertilizer for your lawn, use compost instead of artificial fertilizer.) What you lose in N₂O you’ll more than make up in carbon capture.

2. A hand mower is best, but if you must use a power mower, use an electric mower and contract with your utility for only renewable power (possible in Northeast Ohio, but not advertised). By the time those utility-provided electrons get to your house, they won’t know whether they were generated by coal or wind, but at least you’ll be supporting the renewable contribution to the system. Your lawn will become a net sequesterer of carbon, at least on paper, in anticipation when you’ll have your own home-generated renewable electricity.

3. Still, growing as many trees as possible, especially food forests, is your most responsible option.